The disparity in provision, access and continuation in sport between males and females is evident from childhood. Females undergo significant physical and psychological changes during puberty, which can affect both physical performance and engagement in sports. Strength and conditioning (S&C) coaches have a key role to play in ensuring adolescent female athletes are being supported to thrive in sports, at all levels. The S&C coach should consider the physiological development of the athlete, the environmental factors and how their coaching delivery may be used as a vehicle to ensure the continuation, and indeed success, of female adolescent athletes in sport. This review article presents reflective questions to aid coaching delivery and a coaching framework which considers wider holistic factors that may be important for the successful coaching of adolescent female athletes.

Sports are a popular and well-established means of promoting physical and mental health in children and adolescents.2 However, sex-based disparities in physical activity levels are evident from early childhood,63 with females consistently demonstrating lower engagement than males – a trend which continues into later developmental stages and adulthood.48,63 There are a range of factors – organisational, environmental, sociological, and intra- and interpersonal – which affect participation in sports at all ages.24 Unfortunately, during adolescence – defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as the period of time between ages 10-19 years – the drop-out from sport is high, especially for females.71 Indeed, by the age of 14, females are dropping out of sport at twice the rate of males.73 Although limited funding and limited opportunities may contribute to this trend, enjoyment and self-perceived competence consistently emerge as key factors influencing whether adolescent females continue participating in sport.28,68

Puberty, occurring generally around the ages of 9-12 years for females,36 is characterised by increased body mass, increased height, breast growth and onset of menstruation, all of which can be a source of emotional stress for females engaged in sport, which in turn, may affect their enjoyment of physical activity.73 These physiological changes can affect co-ordination, flexibility and strength, impacting overall movement competency and skill.5 Specifically, sudden increases in limb length can cause specific areas of muscle tightness, negatively impacting overall flexibility10 which, in turn, affects motor coordination.22

Appropriate training interventions around puberty may have the potential to minimise some of these factors. Furthermore, given the fact that enjoyment and self-perception of competence are two factors which may be enhanced by competent coaching, it would seem S&C coaches may be well placed to have a positive impact on the continued engagement in sport for adolescent female athletes. With the rise of S&C provision within school and academy environments, the S&C coach has a key role to play in ensuring coaching of female athletes is set up to support ongoing development and to ensure the continued enjoyment of sport and physical activity throughout these formative years; a trend which is hoped to then continue into adulthood.

Miller and Siegel41 noted that participation in organised youth sport and adult levels of physical activity may be contingent on how positively the experience of youth sport is perceived. With that consideration, exploring coaching considerations for those working with adolescent female athletes seems of paramount importance to review the continuation gap between male and female athletes during the formative adolescent years, and in the interest of informing best coaching practice. To support coaches in applying these considerations in practice, this review will later introduce the Engage–Enthuse–Empower (EEE) framework37 as a guiding approach to coaching delivery with adolescent female athletes.

Female physical development during adolescence introduces several performance-relevant changes that must be considered holistically. Although it is beyond the scope of this article to explore these physiological changes in depth, a summary of key changes is detailed below, an understanding of which is critical for the S&C coach, given these factors will influence performance, training prescription and – most importantly – day-to-day coaching delivery. For a more detailed examination of the menstrual cycle and subsequent coaching considerations, readers are directed to Pitchers and Elliott-Sale.51

During puberty, significant physiological changes occur, including shifts in body composition, hormonal profile, neuromuscular control and growth rate, all of which influence training response and performance potential. Thus, puberty is an important consideration for any coach working with adolescent athletes. Previous work has discussed the Youth Physical Development model for coaching implications,36 and Monasterio et al43 summarise methods to estimate maturity status and timing. Here, it is useful to distinguish between maturity status (where an individual is within their developmental trajectory) and maturity timing (whether maturation occurs earlier, on-time, or later relative to peers). It is also important to note that athletes of the same chronological age can differ considerably in their biological maturity, meaning that two athletes of the same age group may present with very different physical, neuromuscular and psychosocial profiles.

Athletes with an advanced maturity status (eg, post-peak height velocity versus pre-peak height velocity) are recognised to carry a physical advantage,4 implying that early maturing athletes are likely to carry a short-term physical advantage over their later maturing peers. However, this advantage may diminish as later maturing peers ‘catch up’ in strength, coordination and performance capacity through mid-to-late adolescence. Moreover, the lack of data existing in female-specific populations must be considered: only 8% of participants in the Baker et al4 meta-analysis were female. Nonetheless, coaches should therefore consider the benefits and challenges at either end of the maturation spectrum, and how these may affect training and competition environments.21,62 It is also important to note that maturity timing can influence body composition trajectories and psychosocial development in girls. Early maturing females may experience greater gains in fat mass and lower perceptions of physical self-worth and body attractiveness.20

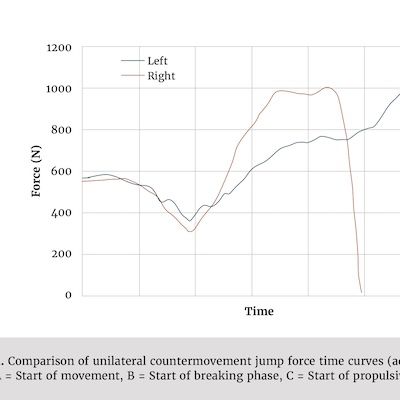

Maturity status and growth rate are also linked with injury risk;47 however, as highlighted by current reviews,4,47 more female-specific research is needed to better understand sex-specific injury mechanisms, such as the higher incidence of ACL injury in adolescent females. Post-pubertal girls are more likely to exhibit kinematic risk factors for ACL injury – such as increased peak knee abduction moment – compared to pre-pubertal peers,53 so this may provide a key future research directive as well as being a consideration for coaches working with these populations.

Puberty typically begins around two years earlier in girls than boys,36 so this has implications for coaching provision. Specifically, younger age groups may be overlooked at a time when structured S&C input could be most impactful – particularly prior to peak height velocity. It is likely that children can benefit most when S&C programmes are implemented prior to the onset of puberty, as early interventions harness peak neuromuscular plasticity to solidify fundamental movement skills, foster tissue adaptation and build a foundational strength base for progressive overload.45 Despite this, females commonly begin organised sport later in childhood and dropout at greater rates than males during their early teens.73 Moreover, where young girls are engaged in organised academy structures, they receive less hours of S&C coaching in comparison to boys and with less experienced coaches.59 This foreshortens the time window available to build foundational movement skills and overall physical literacy, factors which may be further compounded by the quality of S&C provision available, as will be discussed in the following section, ‘Barriers to female participation’.

One of the key changes during female growth and development is the onset of menstruation, with the average age of menarche approximately 12 years of age.67 However, cycles are often irregular and unpredictable in early adolescence,50,67 reflecting the immaturity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis;8 it is possible that girls are more sensitive to hormonal fluctuations at this stage due to the relative novelty of these processes. Premenstrual symptoms are common in adolescents, often peaking in severity during the late teenage years.15,42 The organisation Women in Sport69 found that 7 in 10 girls avoid physical activity during their period, with pain, fear of leakage, and tiredness cited as key barriers. Coaches should be aware of these factors and prepared to adjust training where appropriate to support athlete well-being and performance. Involving parents into any training or well-being conversations plays an important role; first, it helps to normalise open dialogue around menstrual cycle factors, and second, it may provide the coach with additional information around athlete concerns, or relevant socioeconomic factors which may be influencing their experiences.46

It is important to emphasise to young female athletes that they can train and perform at any stage of their menstrual cycle,17,40 minimising the potential for any nocebo effect. However, hormonal and symptom fluctuations across the menstrual cycle may affect factors such as neuromuscular control, pain perception and fatigue levels on an individual basis.31 Educating athletes about how their bodies may feel or perform across their cycle, and encouraging open dialogue, can help foster autonomy and self-awareness in managing training loads and recovery.

Breast tissue typically begins to develop between the ages of 8 and 12.6 Because of their mass and movement, breast tissue causes a number of biomechanical alterations;39 wearing a correctly fitted sports bra has been shown to lead to improved running economy26 and ACL-favourable kinematics during drop landings.25 Poorly fitted or absent support can lead to increased breast movement, discomfort, and self-consciousness – particularly during high-impact activity or mixed-gender training settings. Scurr et al57 reported that nearly half of school-aged girls in the UK avoid physical activity due to breast-related discomfort or embarrassment. This underlines the importance of early education around supportive kit and establishing good habits for sports participation.

Baker and Davison3 highlighted that more advanced breast development at a younger age was associated with greater relative declines in perceived athletic competence, independent of exposure levels to physical activity. The authors went on to suggest that puberty of young female athletes should be a key time for coaches to focus on developing athletes’ confidence and perceived competence. Normalising body development via open dialogue around comfort, symptoms and confidence should be actioned by all coaches working with adolescent female athletes. The use of positive role models may also be a powerful tool in normalising physical development in this instance and provide additional reassurance.49

Despite the importance of breast support for comfort and performance, many adolescent girls lack access to appropriate sports bras, either due to financial barriers, lack of knowledge or embarrassment discussing the topic. Coaches should be aware that breast development can be a sensitive issue for girls; as such, they must be prepared to take sensitive, proactive steps to normalise discussions around kit, ensure privacy in changing facilities and collaborate with schools or clubs to provide guidance on supportive sportswear. All this may help increase confidence in physical activity settings.

Although biological development plays an important role in the experience of adolescent female athletes, this is equally shaped by the social and cultural context to which each individual is exposed. Girls face several unique challenges to participating and thriving in sport – some overt, others more subtle, yet all have the potential to reduce their engagement with sport and physical activity. Strength and conditioning coaches are often well-placed to help address some of these barriers; however, doing so requires an awareness of these issues, conscious reflection and the desire to be an agent of positive change.

Girls’ teams are often treated as a lower priority compared to boys’ teams.69 This can be reflected in inferior facilities, less desirable training or competition times, reduced funding for equipment and kit, and limited access to experienced or specialist coaching staff. Young female athletes are rarely offered S&C programmes comparable to male counterparts;59 indeed, Reynolds et al54 identified that coaches who designed S&C programmes for female athletes were less likely to be certified than those working with male athletes. It is critical that organisations seek to address this disparity in order to provide young adolescent female athletes the same opportunities afforded to their male counterparts, particularly given the earlier onset of puberty, and the reflection that key physical development opportunities may be being missed for young female athletes.

Concerns regarding changing facilities, privacy and the availability of female-friendly spaces within training environments are all potential factors discouraging girls from engaging in sport.29 Inadequate facilities may make girls feel that their needs have not been considered, contributing to a sense of exclusion from the sporting environment. For example, the absence of menstrual hygiene products or private disposal options in changing facilities can heighten anxiety during menstruation. Issues with sports kit can also create barriers for adolescent girls, particularly around enforced wearing of pale colours and perceived concerns around modesty.40 Often, girls are provided with kit designed for boys, which does not accommodate the needs of the developing female body; clubs are therefore encouraged to involve young female athletes in discussions around kit requirements, rather than taking a dictatorial approach.

From an early age, girls and boys are exposed to different messages which shape perceptions regarding body image and physicality.11,30 Concerns over body shape and composition – such as getting ‘bulky’ – may lead to some of the common misgivings and hesitancy of female athletes to engage with physical training.58 Specifically, strength and conditioning training can often be perceived as an extension of male-coded sport culture, with connotations of muscle gain and body image concerns that can deter girls from engaging with training that would benefit their health, performance and confidence. Education can go some way to offsetting these concerns, and coaches should be encouraged to initiate open dialogue with young female athletes around body development, while also using role model examples from their chosen sports. Fortunately, the currently evolving landscape presents a more encouraging picture, with female participation in sports such as football and rugby growing globally with international bodies recognising the need to increase both visibility and exposure of female sport.14,65 However, the continued underrepresentation of women in coaching and leadership roles within many sports – including strength and conditioning coaches63 – can reinforce these gendered perceptions, influencing both the opportunities available to girls and the environments in which they train. Indeed, in the United Kingdom, less than 10% of UKSCA accredited S&C coaches are female.

Explicit personality traits are also recognised to differ between genders, probably driven by social norms and stereotypes.66 Traits traditionally associated with athletic achievement – for example, competitiveness, assertiveness and risk-taking – are frequently viewed as more desirable for boys.23 Coaches should be aware of the need to actively integrate these values into their coaching delivery of sessions for young female athletes. Krane et al34 describes a paradox between the traditionally masculine culture of sport and the overall social climate which values femininity in girls. Navigating this social inconsistency – or ‘femininity deficit’16 – is a threat to sport participation.61 Participation patterns often mirror gendered expectations within society, with ‘male-coded’ sports such as football, rugby, and weightlifting often seen as less appropriate for girls, whereas activities emphasising aesthetics or cooperation are more strongly associated with femininity.7,11 This gendered segregation can limit opportunities, reduce exposure to a variety of sports, and prevent girls from exploring activities that might foster physical confidence and competence.

Girls and boys often develop different attitudes toward sport, risk, and self-efficacy, shaped by both social expectations and internal psychological factors. For example, Women in Sport70 report that although 52% of boys aspire towards reaching the top level in sport, only 29% of girls share that ambition. Lack of funding was the most cited barrier, but the second most common reason was that girls are simply not encouraged to excel in sport to the same degree as boys.70 During adolescence, girls face heightened social and psychological pressures. Fear of judgement is a major barrier to participation – whether due to appearance concerns, fear of making mistakes, or anxiety about being seen as ‘not good enough’.59 These fears can hold girls back from pushing themselves in training or engaging confidently in competitive environments. Females may also be more sensitive to social feedback, especially from peers or authority figures, which can shape how they view themselves as athletes.33 Female adolescents also often exhibit lower self-efficacy compared to male peers, which may contribute to lower levels of physical activity.60 Moreover, although self-efficacy correlates with activity in both genders, it is a particularly strong predictor for girls.60

Appropriate and successful coaching of all athletes should be driven by an evidence-based approach. However, the lack of research into the efficacy of programming for female adolescent athletes is concerning: in a systematic review aiming to determine the most effective resistance training protocol for adolescent athletes, only 11% of studies which met required inclusion criteria focused on female athletes.35 In a similar systematic review, Sommi et al59 found only 9% of reviewed studies investigated adolescent female athletes, compared to 91% male-focused studies. This research bias is continued for senior female athletes also, with Cowley et al18 highlighting that a review of 5000 papers from six sports medicine and exercise sciences journals presented only 6% of manuscripts that focused solely on female athletes. This concerning disparity presents clear evidence that more research is needed to investigate S&C practices for female athletes of all ages, in order for practitioners to optimise their long-term development strategies. However, Roche et al55 suggested there is a growth of research in this area over recent years, concurrent with increasing interest in female sports. It is hoped this growth will filter down into increasing research and subsequent provision for female athletes across all ages.

Numerous negative physical outcomes are associated with lack of physical training for both males and females, so the question remains as to whether youth female athletes are being set up to fail with the lack of female-specific research. One of the primary challenges of training adolescent athletes is the different rates of biological maturation and psychosocial development of each individual.27 As such, there is a need for individualised programming considering individual needs, yet as previously discussed, funding and provision for this may be lacking in a female-athlete setting.

Having outlined the physiological and socio-cultural contexts shaping adolescent female athletes, it is essential to consider how coaches can translate these insights into day-to-day practice. Self-determination theory (SDT) proposes three basic psychological needs – autonomy, competence and relatedness – which, when fulfilled, are associated with heightened well-being and intrinsic motivation.32,56 S&C coaches can have significant impact on an athlete’s enjoyment and motivation; the motivational climate they establish will determine whether or not girls continue to engage with training and sport.12,68 Drawing on SDT provides a useful way to translate theory into effective practice for this population. Building on this, the Engage–Enthuse–Empower framework37 provides a practical lens through which S&C coaches can consider their performance with adolescent female athletes.

Engagement is the foundation of sustained participation. For girls to engage with strength and conditioning, they must feel a sense of competence and psychological safety. A coach’s feedback and communication style are central here: perceptions of competence are heavily shaped by how coaches value and recognise their athletes’ abilities.9 Frequent encouragement, constructive corrections, and recognition of effort have been shown to increase perceived competence and overall satisfaction, particularly among adolescent females.1 Conversely, negative behaviours such as punishments, sarcasm, or dismissive ‘banter’ can heighten anxiety and contribute to dropout risk.19 Qualified coaches with strong technical and interpersonal skills are therefore essential to creating a training environment where girls feel capable and motivated to engage.

Once engaged, enjoyment and belonging become key drivers of continued participation. Social identity – feeling part of a valued group – is particularly influential for adolescent girls, with links to greater self-worth, effort, and commitment.38,44 Coaches can foster this by designing sessions that include partner or team-based tasks, opportunities for peer feedback and challenges that require cooperation as well as competition. These practices strengthen relatedness and increase the likelihood that athletes will associate training with positive emotions. Enjoyment and social connectedness consistently emerge as two of the strongest predictors of girls’ long-term sport involvement.44 Coaches should also be mindful of how peers can affect an athlete’s perception of competence13 and therefore must strive to create an environment where athletes are supportive of one another.

When athletes feel empowered, they begin to take greater ownership of their sporting journey – developing autonomy, self-regulation, and the capacity to sustain motivation beyond external pressures.72 Evidence suggests that coaches have the strongest role in shaping athletes’ sense of autonomy and competence.13 Coaches can encourage this by involving athletes in aspects of session planning, prompting reflection on how training affects their bodies and performance, and gradually encouraging independent decision-making. Simple tools, such as asking athletes to track their progress or identify personal strengths, can reinforce autonomy. Over time, this sense of empowerment not only supports retention in sport but also builds transferable life skills in confidence, resilience and self-efficacy.

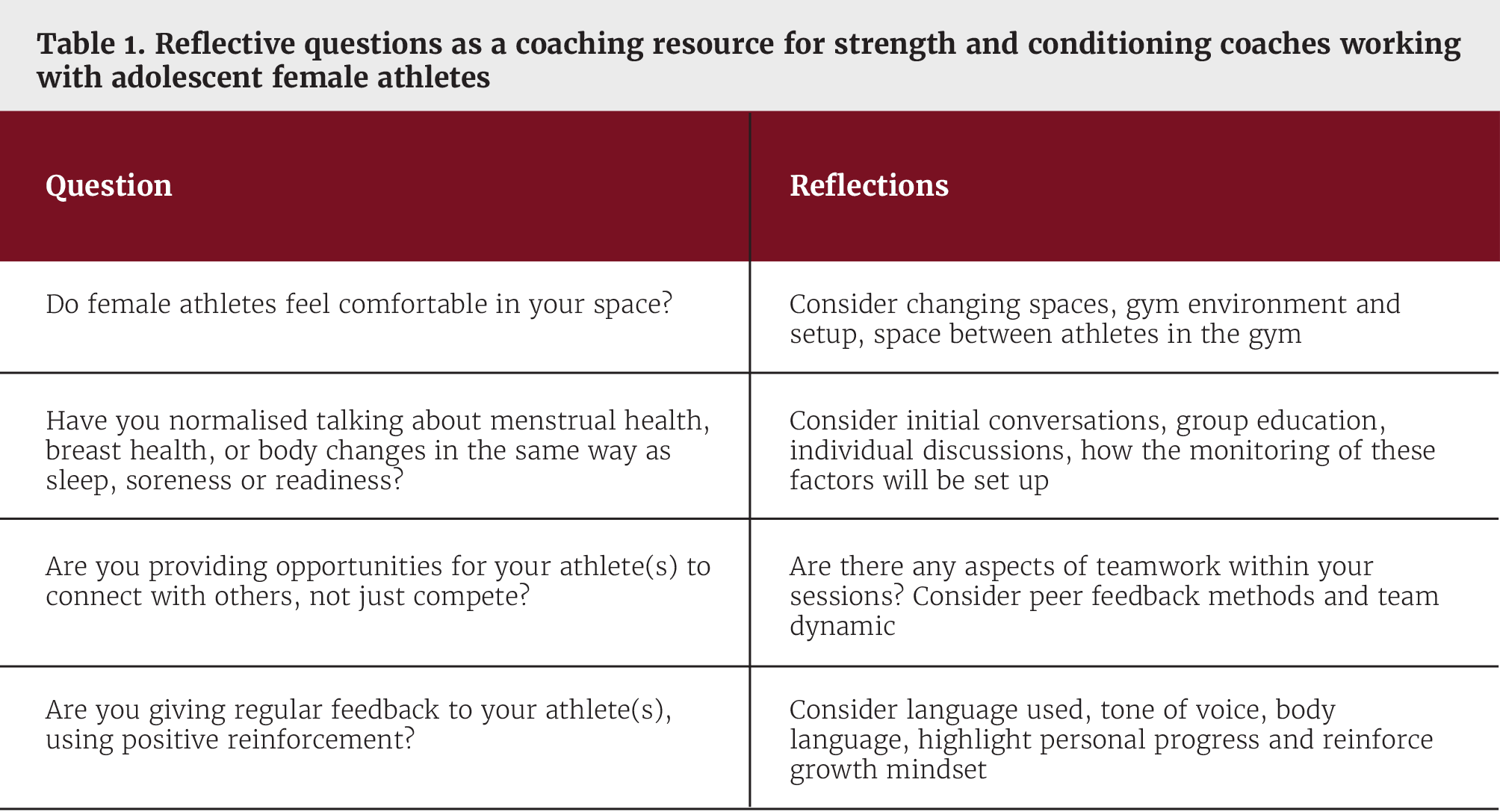

Coaches working with adolescent athletes should aim to maximise athlete enjoyment and self-perception of competence, which may lead to subsequent increases in athlete confidence, and reduce the likelihood of drop out. Strength and conditioning coaches working with adolescent female athletes may choose to use the questions in Table 1 as reflective practice, with a review to optimising their delivery.

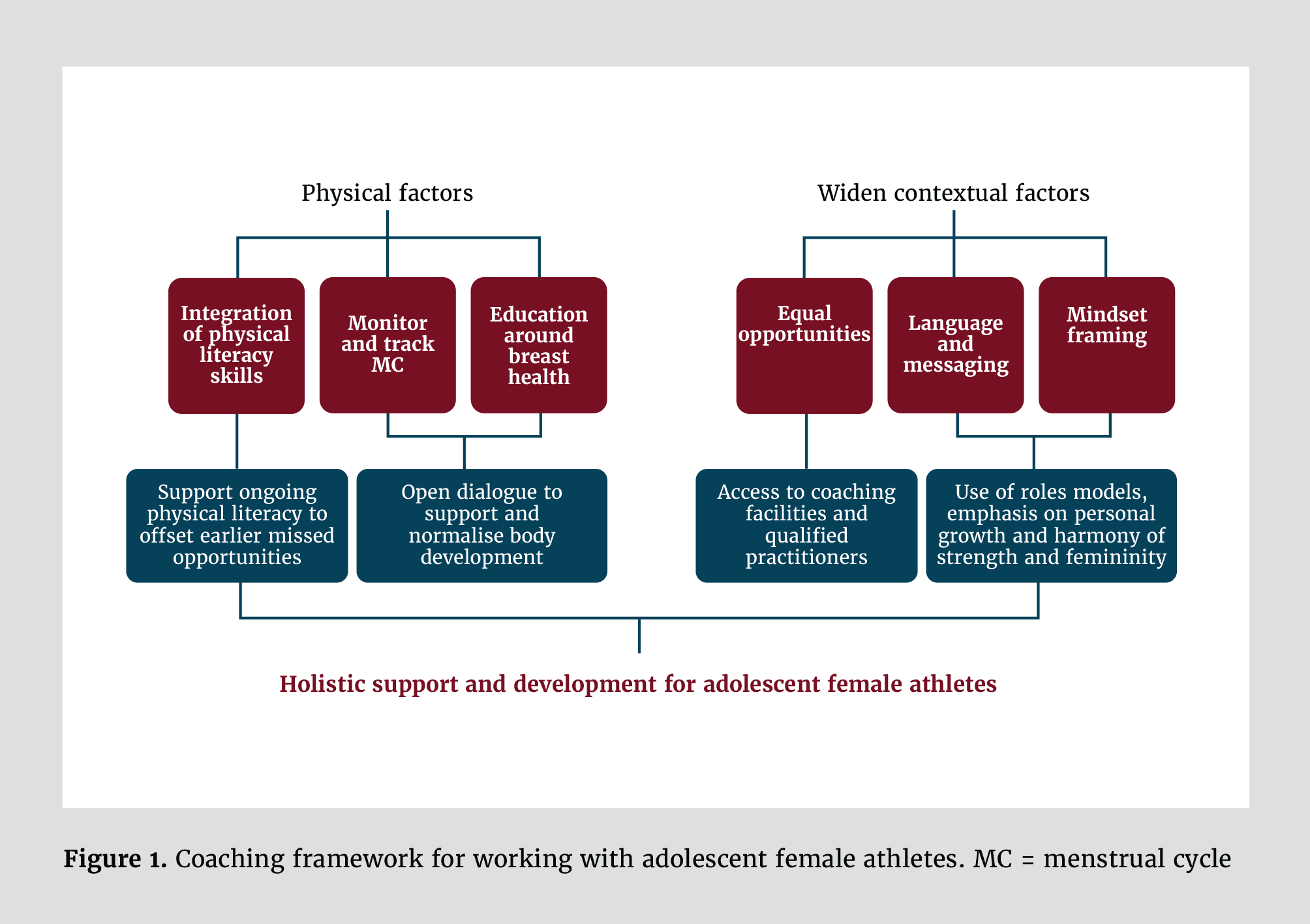

Figure 1 presents a coaching framework for S&C coaching provision to adolescent female athletes. The key coaching implications suggest the need for consideration of both physical factors, and wider contextual factors, both brought together by an experienced coaching delivery with open dialogue around key issues female athletes face.

Despite progress in recent years, research into adolescent female athletes remains limited compared to that into their male counterparts. Further investigation is needed to understand the unique female developmental, psychological, and social contexts. Evidence suggests that S&C programmes for female athletes should ideally be implemented prior to the onset of puberty and be delivered by suitably qualified coaches. However, barriers such as limited funding and reduced opportunities for young female athletes can restrict access, leaving some female athletes with lower levels of physical literacy in later adolescence and beyond. To address this, programmes must not only build physical competence but also provide regular opportunities to revisit and reinforce fundamental movement skills.

Strength and conditioning coaches have a pivotal role in shaping adolescent females’ engagement, enjoyment, and empowerment in sport. By fostering competence through positive reinforcement, supporting social identity through teamwork and peer interaction, and encouraging autonomy through athlete ownership, coaches can create environments that both retain young women in sport and equip them with transferable life skills. Coaches should consider this text as a call to action, to review their practice around coaching provision and coaching delivery of adolescent female athletes: Table 1 provides a resource for coaching reflection for those working within this space. Ultimately, effective coaching with this population has the potential to not only sustain sporting participation but also enhance health, well-being, and confidence into adulthood.

1. Allen, J.B. and B. Howe. Player ability, coach feedback, and female adolescent athletes' perceived competence and satisfaction. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 20(3): 280-299. 1998.

2. Back, J., et al. Drop-out from team sport among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 61: 102-205. 2022.

3. Baker, B.L. and K.K. Davison. I know I can: a longitudinal examination of precursors and outcomes of perceived athletic competence among adolescent girls. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 8(2): 192-199. 2011.

4. Baker, J., et al. Differences in sprinting and jumping performance between maturity status groups in youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 55(6): 1405-1427. 2025.

5. Beunen, G. and R.M. Malina. Growth and biologic maturation: relevance to athletic performance. The Young Athlete, 1: 3-17. 2008.

6. Biro, F.M., et al. Onset of breast development in a longitudinal cohort. Pediatrics, 132(6): 1019-1027. 2013.

7. Bowker, A., S. Gadbois, and B. Cornock. Sports participation and self-esteem: Variations as a function of gender and gender role orientation. Sex Roles, 49(1-2): 47-58. 2003.

8. Calcaterra, V., et al. Menstrual dysfunction in adolescent female athletes. Sports, (9): 245. 2024.

9. Cecchini, E., J. Fernández-Rio, and A. Méndez-Giménez. Connecting athletes’ self-perceptions and metaperceptions of competence: a structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Human Kinetics, 46: 189-198. 2015.

10. Chagas, D.D.V. and L.M. Barnett. Adolescents’ flexibility can affect motor competence: The pathway from health related physical fitness to motor competence. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 130(1): 94-111. 2023.

11. Chalabaev, A., et al. The influence of sex stereotypes and gender roles on participation and performance in sport and exercise: Review and future directions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(2): 136-144. 2013.

12. Chan, D.K., C. Lonsdale, and H.H. Fung. Influences of coaches, parents, and peers on the motivational patterns of child and adolescent athletes. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports,22(4): 558-568. 2012.

13. Chu, T.L. and T. Zhang. The roles of coaches, peers, and parents in athletes’ basic psychological needs: a mixed-studies review. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 14(4): 569-588. 2019.

14. Clargo, B. and M. Skey. 'Forgive me for saying, but rugby is not a game for women': an exploration of contemporary attitudes towards women’s rugby union. European Journal for Sport and Society, 22(1): 52-66. 2025.

15. Cleckner-Smith, C.S., A.S. Doughty, and J.A. Grossman. Premenstrual symptoms: prevalence and severity in an adolescent sample. Journal of Adolescent Health, 22(5): 403-408. 1998.

16. Cockburn, C. and G. Clarke. “Everybody's looking at you!”: Girls negotiating the “femininity deficit” they incur in physical education. Women's Studies International Forum, 25(6): 651-665. 2002.

17. Colenso-Semple, L.M., et al. Current evidence shows no influence of women’s menstrual cycle phase on acute strength performance or adaptations to resistance exercise training. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5: 1054542 2023.

18. Cowley, E.S., et al. “Invisible Sportswomen”: the sex data gap in sport and exercise science research. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal, 29(2):146-151. 2021.

19. Cumming, S.P., et al. Body size and perceptions of coaching behaviors by adolescent female athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 6(6): 693-705. 2005.

20. Cumming, S.P., et al. Maturational timing, physical self-perceptions and physical activity in UK adolescent females: investigation of a mediated effects model. Annals of Human Biology, 47(4): 384-390. 2020.

21. Cumming, S.P., et al. Biological maturation, relative age and self-regulation in male professional academy soccer players: A test of the underdog hypothesis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 39:147-153. 2018.

22. Davies, P.L. and J.D. Rose. Motor skills of typically developing adolescents: awkwardness or improvement? Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 20(1): 19-42. 2020.

23. Deaner, R.O., S.M. Balish, and M.P. Lombardo. Sex differences in sports interest and motivation: an evolutionary perspective. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 10(2): 73-97. 2016.

24. Eime, R.M., J.T. Harvey, and M.J. Charity. Sport drop-out during adolescence: is it real, or an artefact of sampling behaviour? International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 11(4): 715-726. 2019.

25. Fong, H.B., et al. Greater breast support alters trunk and knee joint biomechanics commonly associated with anterior cruciate ligament injury. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4: p. 861553 2022.

26. Fong, H.B. and D.W. Powell. Greater breast support is associated with reduced oxygen consumption and a greater running economy during a treadmill running task. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4: 902-276. 2022.

27. Gabbett, T. Training the adolescent athlete. Sports Health, 14(1): 11-12. 2022.

28. Gredin, N.V., et al. Exploring psychosocial risk factors for dropout in adolescent female soccer. Science and Medicine in Football, 6(5): 668-674. 2022.

29. Hanlon, C., C. Jenkin, and M. Craike. Associations between environmental attributes of facilities and female participation in sport: a systematic review. Managing Sport and Leisure, 24(5): 294-306. 2019.

30. He, J., et al. Meta-analysis of gender differences in body appreciation. Body Image, 33: 90-100. 2020.

31. Iacovides, S., I. Avidon, and F.C. Baker. Does pain vary across the menstrual cycle? A review. European Journal of Pain, 19(10): 1389-1405. 2015.

32. Jowett, S., et al. Motivational processes in the coach-athlete relationship: a multi-cultural self-determination approach. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 32: 143-152. 2017.

33. Kamal, A.F., et al. Informational feedback and self-esteem among male and female athletes. Psychological Reports, 70(3): 955-960. 1992.

34. Krane, V., et al. Living the paradox: Female athletes negotiate femininity and muscularity. Sex Roles, 50(5-6): 315-329. 2004.

35. Lesinski, M., O. Prieske, and U. Granacher. Effects and dose–response relationships of resistance training on physical performance in youth athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(13): 781-795. 2016.

36. Lloyd, R.S. and J.L. Oliver. The Youth Physical Development Model: a new approach to long-term athletic development. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 34(3): 61-72. 2012.

37. Maloney, S.J. Engage, Enthuse, Empower: A framework for promoting self-sufficiency in athletes. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 45(4):486-497. 2023.

38. Martin, L.J., et al. The influence of social identity on self-worth, commitment, and effort in school-based youth sport. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(3): 326-332. 2018.

39. McGhee, D.E. and J.R. Steele. Breast biomechanics: what do we really know? Physiology, 35(2): 144-156. 2020.

40. McNulty, K.L., et al. The effects of menstrual cycle phase on exercise performance in eumenorrheic women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 50(10): 1813-1827. 2020.

41. Miller, S.M. and J.T. Siegel. Youth sports and physical activity: the relationship between perceptions of childhood sport experience and adult exercise behavior. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 33: 85-92. 2017.

42. Mitsuhashi, R., et al. Factors associated with the prevalence and severity of menstrual-related symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1): 569. 2023.

43. Monasterio, X., et al. Estimating maturity status in elite youth soccer players: Evaluation of methods. Medicine & Science in Sport & Exercise, 56(6): 1124-1133. 2024.

44. Murray, R.M. and C.M. Sabiston. Understanding relationships between social identity, sport enjoyment, and dropout in adolescent girl athletes. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 44(1): 62-66. 2022.

45. O'Brien, W., S. Belton, and J. Issartel. Fundamental movement skill proficiency amongst adolescent youth. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 21(6): 557-571. 2016.

46. O'Loughlin, E., D. Reid, and S. Sims. Discussing the menstrual cycle in the sports medicine clinic: perspectives of orthopaedic surgeons, physiotherapists, athletes and patients. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 15(1): 139-157. 2023.

47. Parry, G.N., et al. Associations between growth, maturation and injury in youth athletes engaged in elite pathways: a scoping review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 58(17): 1001-1010. 2024.

48. Pate, R.R., et al. Age-related change in physical activity in adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44(3): 275-282. 2009.

49. Pell, B., et al. CHoosing Active Role Models to INspire Girls (CHARMING): protocol focluster randomised feasibility trial of a school-based, community-linked programme to increase physical activity levels in 9–10-year-old girls. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 8(1): 2. 2022.

50. Peña, A.S., et al. The majority of irregular menstrual cycles in adolescence are ovulatory: results of a prospective study. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 103(3): 235-239. 2018.

51. Pitchers, G. and K. Elliott-Sale. Considerations for coaches training female athletes. Professional Strength and Conditioning, 55: 19-30. 2019.

52. Radnor, J., Moeskops, S., Morris, S., Mathews, T., Kumar, N., Pullen, B., Meyers, R., Pedley, J., Gould, Z., Oliver, J., and Lloyd, R. Developing Athletic Motor Skill Competencies in Youth. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 42(6):54-70. 2020.

53. Ramachandran, A.K., et al. Changes in lower limb biomechanics across various stages of maturation and implications for acl injury risk in female athletes: a systematic review. Sports Medicine, 54(7): 1851-1876. 2024.

54. Reynolds, M.L., et al. An examination of current practices and gender differences in strength and conditioning in a sample of varsity high school athletic programs. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 26(1): 174-183. 2012.

55. Roche, M., et al. How can we better engage female athletes? A novel approach to health and performance education in adolescent athletes. BMJ Open Sport & Execise Medicine, 10(3): e001901. 2024.

56. Ryan, R.M. and E.L. Deci. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1): 68-78. 2000.

57. Scurr, J., et al. The influence of the breast on sport and exercise participation in school girls in the United Kingdom. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(2):167-173. 2016.

58. Shurley, J., et al. Historical and social considerations of strength training for female athletes. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 42(4): 22-35. 2020.

59. Sommi, C., et al. Strength and conditioning in adolescent female athletes. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 46(4): 420-426. 2018.

60. Spence, J.C., et al. The role of self-efficacy in explaining gender differences in physical activity among adolescents: a multilevel analysis. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 7(2): 176-183. 2010.

61. Spencer, R.A., L. Rehman, and S.F.L. Kirk. Understanding gender norms, nutrition, and physical activity in adolescent girls: a scoping review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12: 6. 2015.

62. Sweeney, L., J. Taylor, and A. MacNamara. Push and pull factors: Contextualising biological maturation and relative age in talent development systems. Children, 2023. 10(1): p. 130.

63. Thomas, G., K. Devine, and G. Molnár, Experiences and perceptions of women strength and conditioning coaches: a scoping review. International Sport Coaching Journal, 2023. 10(1): p. 78-90.

64. Troiano, R.P., et al.. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Medicine & Science in Sport & Exercise, 2008. 40(1): p. 181-188.

65. Valenti, M., N. Scelles, and S. Morrow. The determinants of stadium attendance in elite women’s football: evidence from the FA Women’s Super League. European Sport Management Quarterly, 25(2): 322-338. 2025.

66. Vianello, M., et al. Gender differences in implicit and explicit personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(8): 994-999. 2013.

67. Wang, Z., G. Asokan, and J.-P. Onnela. Menarche and time to cycle regularity among individuals born between 1950 and 2005 in the US. JAMA Network Open, 7(5):1-15. 2024,

68. Weiss, M.R., A.J. Amorose, and A.M. Wilko. Coaching behaviors, motivational climate, and psychosocial outcomes among female adolescent athletes. Pediatric Exercise Science, 21(4): 475-492. 2009.

69. Women in Sport. Reframing sport for teenage girls: Tackling teenage disengagement. Sport England. 2022.

70. Women in Sport. Daring to dream: The gender dream deficit in sport. Sport England. 2023.

71. Zarrett, N., P.T. Veliz, and D. Sabo. Keeping Girls in the Game: Factors That Influence Sport Participation. New York, NY. 2020.

72. Zhang, N., G. Du, and T. Tao. Empowering young athletes: the influence of autonomy-supportive coaching on resilience, optimism, and development. Frontiers in Psychology, 15: 1433171. 2025.

73. Zwolski, C., C.C. Quatman-Yates, and M.V. Paterno. Resistance training in youth: laying the foundation for injury prevention and physical literacy. Sports Health, 27(9): 436-443. 2017.

Julie has led a variety of athlete scholarship programmes within schools and universities producing athletes through a pathway from grassroots to elite levels. She has a degree in Sports Therapy, an MSc in S&C, she has been a UKSCA Accredited Coach since 2009 and has over 15 years of experience in both sports therapy and S&C roles, supporting athletes to two Olympic Games and working within a wide range of sports. Julie is currently completing her PhD, investigating female athlete sleep habits, and the effects of sleep hygiene on performance.

Sean is the founder of Maloney Performance, a high-performance strength and conditioning service supporting athletes and teams across multiple sports. He also leads Palestra Education; a coach development initiative focused on translating sport science and pedagogical principles into practical learning.