Sean J Maloney, PhD, ASCC, CSCS, Maloney Performance

This article explores how S&C coaches can expand their role to become allies in the world of mental health, going beyond performance enhancement to foster environments where athletes can thrive both physically and mentally. By developing an awareness of common mental health issues, creating a supportive atmosphere, and recognising early warning signs, S&C coaches can play a critical role in safeguarding their athletes' well-being. The goal is not to replace mental health professionals, but to complement their work by embedding proactive, athlete-centred practices into daily interactions. This approach benefits athletes, while also reinforcing the coach-athlete relationship, ultimately enhancing both performance and personal development.

In recent years, the conversation around mental health in sport has gained momentum, shedding light on the challenges faced by athletes at all levels.1 Although the physical demands of training and competition are well-documented, the psychological pressures that accompany athletic performance often remain in the shadows. Strength and conditioning (S&C) coaches, as trusted figures in athletes’ lives, are uniquely positioned to bridge this gap. Despite increased awareness, stigma around mental health persists, particularly in high-performance environments where athletes may feel pressure to appear mentally resilient. As a result, many athletes are reluctant to seek help or even acknowledge their struggles. This reluctance underscores the importance of S&C coaches, who often interact with athletes daily and build relationships based on trust and open communication.

Multiple studies have examined the prevalence of mental health issues in athletes across various sports, highlighting significant concerns in both elite, amateur and youth athletes. Mental health challenges do not discriminate by performance level; they can arise from the unique pressures of sport, personal life stressors, or broader societal issues. Although some individuals may thrive under the demands of competition, others may struggle to cope with setbacks, injuries, or transitions in their careers.

In separate meta-analyses, Gorczynski et al17 and Rice et al46 have reported that elite athletes demonstrate a similar prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms, respectively, to the general population. These findings challenge the assumption that athletes, by virtue of their fitness or resilience, are less susceptible to mental health struggles.1 At its core, mental health is a fundamental aspect of being human, not something negated by athletic ability. Although sport can provide protective factors such as structure, social support, and physical activity, it does not make athletes immune to the psychological challenges that affect everyone. Additionally, some specific conditions, such as disordered eating or exercise addiction, may occur more frequently in athletic populations. For instance, Sundgot-Borgen and Torstveit51 reported a higher prevalence of disordered eating behaviours among athletes (13.5%) compared to non-athletes (4.6%), particularly in sports with a focus on weight or aesthetics. Similarly, Dorfling and Fulcher9 reported higher prevalence of alcohol misuse and gambling in New Zealand Super Rugby players.

Gulliver et al22 reported that 46.4% of elite Australian athletes experienced symptoms of at least one mental health condition, including depression (27.2%) and generalised anxiety disorder (7.1%). Injured athletes were particularly vulnerable, demonstrating significantly higher rates of both depression and anxiety. Similarly, Foskett and Longstaff14 found that 47.8% of elite UK athletes showed signs of anxiety or depression, with career dissatisfaction emerging as a significant predictor of these issues. A recent meta-analysis suggests that female athletes are more likely to report anxiety, depression, distress, and disordered eating, whereas male athletes report more substance misuse and gambling.32

In sport-specific contexts, these mental health challenges also appear prevalent. Among Swiss football players, Junge and Feddermann-Demont30 reported that, although the prevalence of depression mirrored that of the general population, younger male U-21 players exhibited higher incidence than female or older players. Injuries, playing positions, and conflicts with coaches were common contributors. Female footballers in the German First League, as noted by Prinz et al,43 reported a career prevalence of depression symptoms at 32.3%, with conflicts with management and inadequate support from coaches cited as primary stressors. Alarmingly, 40% of these players wanted or needed psychological support during their careers, yet only 10% accessed it. Bilgoe et al5 extended these findings, demonstrating that sport-specific psychological distress persisted over a 12-month follow-up period among female professional football players, ranging from 53% to 65% depending on the time point. Disordered eating also remained consistently prevalent (15%-20%).

The significant prevalence of mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, disordered eating and distress, among athletes highlights an urgent need for intervention. Under-reporting likely remains a critical barrier, driven by stigma, cultural norms, and fears of professional repercussions.8,21

Athletes face unique challenges that impact their mental health, which can be broadly categorised into sport-specific, environmental/cultural factors and career/family stressors. Injuries are a prominent sport-specific stressor, often leading to feelings of isolation, frustration, and identity loss during rehabilitation. Injured athletes report higher levels of depression16 and anxiety,46 with those recovering from surgery nearly twice as likely to experience psychological distress.5 Performance pressures, such as high expectations from coaches, fans, and themselves, add further strain, particularly during high-stakes competition.16,54 Specifically, ‘choking’ has been identified as an experience which can negatively affect mental health.23,27 Additionally, burnout from prolonged training and competition cycles without sufficient recovery (ie, ‘overtraining’-related conditions) can diminish motivation, increase emotional exhaustion and contribute to mental health challenges.2,33

Environmental and cultural factors also play a significant role. Organisational stressors, including poor communication, lack of support and financial instability, create uncertainty and distress for many athletes.3 Team dynamics are equally critical as – although positive relationships foster belonging – conflicts, favouritism, or toxic leadership can heighten psychological strain.34 It is possible that cultural norms in sport, particularly the glorification of ‘toughness’ and stigma around mental health, may discourage athletes from seeking help.8,20 Addressing these factors through better organisational practices, education and destigmatisation efforts is essential to supporting athlete well-being.

Athletes face unique life and career transitions that compound the psychological demands of their sporting pursuits. For student athletes, academic and social pressures often intersect with their sporting commitments, creating significant challenges in time management and prioritisation.31 Selection and de-selection into academies, squads or programmes add another layer of stress, with rejection potentially affecting self-worth and sometimes leading to clinical levels of psychological distress.7 Additionally, the transition from junior to high-performance sport, while representing a significant milestone in an athlete’s career, often introduces a foreign environment with heightened pressures and expectations.42 These early experiences can profoundly shape an athlete’s long-term relationship with sport, underscoring the importance of supportive development frameworks during these formative years.42,47

Even at the high-performance level, athletes are not immune to external pressures. Many must balance dual careers, combining sport with education or employment, which may elevate the risk of chronic stress and burnout.35 Financial insecurity is another key concern,3 with some athletes at risk of losing critical funding from government organisations or sponsors due to injury or performance dips. These financial pressures can exacerbate anxiety and leave athletes feeling unsupported by the systems that once backed them.

The transition out of sport is perhaps the most profound challenge athletes face, and it is often beyond their control. Retirement, whether planned or abrupt due to injury or deselection, can lead to identity loss, feelings of purposelessness and difficulty adjusting to life outside of sport.19,48 Without adequate preparation and support, these transitions may result in mental health issues that persist long after an athlete’s career has ended. Addressing these challenges requires a proactive approach, fostering resilience and equipping athletes with the tools to manage the broader demands of life alongside their sporting endeavours.36 These complexities underscore the importance of S&C coaches being aware of the prevalence and nature of mental health challenges in sport to better support athletes at all levels.

Intuitively, creating an atmosphere of psychological safety (PS) would appear crucial for athletes to feel supported and able to express vulnerabilities without fear of judgment or repercussions. Edmondson’s widely adopted definition10 of PS involves two key perceptions: 1) that individuals will not face rejection for expressing themselves or seeking help, and 2) that mistakes will not lead to punitive consequences. Although PS can foster trust and open communication, critical for athlete well-being and team cohesion,11 the realities of high-performance sport – including selection, funding and performance outcomes – can limit its practical applicability.52 Thus, striking a balance is key. Over-emphasising PS may inadvertently create an environment perceived as ‘too safe’, leading to a dilution in standards of performance or undermining competitive rigour.52 This article proposes a revised definition of PS within high-performance sport – building on that of Vella et al53: ‘A group-level perception that team interactions are safe for expressing vulnerability and seeking support, while recognising the performance-driven realities of high-performance sport.’

Ultimately, creating PS in high-performance sport relies not only on the athlete’s individual experience, but also on the collective efforts of the coaching team, support staff and teammates to foster an environment of trust, accountability and mutual respect. Coaches and support staff can lead by example, demonstrating empathy and active listening during conversations with athletes that extend beyond the Xs and Os of performance.29 Establishing regular one-on-one check-ins can help athletes feel heard and also create opportunities to address concerns proactively.44 Indeed, athlete engagement and empowerment should be seen as a key objective for the S&C coach.36 Encouraging a culture where teammates provide constructive feedback, rather than criticism, also nurtures trust, allowing individuals to feel safe discussing challenges, setbacks, and mistakes.53

De-stigmatising mental health discussions is another key component, as has been previously discussed. Normalising conversations about mental well-being may start with integrating mental health education into team meetings or workshops, addressing topics such as stress management, coping strategies and the signs of common mental health issues. Gucciardi et al20 proposes such strategies be implemented under the guise of ‘mental toughness development’ to maximise interest and engagement. Sharing stories of athletes who have successfully navigated mental health challenges, whether from within the team or through external examples, may further dismantle stigma. The frequency of high-profile athletes publicly sharing their own stories has noticeably increased in the last two decades.40 Coaches and leaders should also actively challenge harmful cultural norms, such as the glorification of ‘the struggle’, by promoting self-care and seeking professional support when needed. Encouraging athletes to engage with resources like sports psychologists or other professional services may ensure that mental health becomes an integrated and accepted part of performance optimisation, rather than an afterthought.6

By building trust and reducing stigma, teams can create an environment where athletes feel empowered to prioritise their mental well-being alongside their physical performance.

S&C coaches are uniquely positioned to influence both the physical and psychological well-being of athletes. Their regular, often informal, interactions with athletes create opportunities to build meaningful relationships,15,21,29,45 making them a vital part of the support network. Being approachable and empathetic is fundamental to this role. Athletes are more likely to open up about their struggles when they feel their concerns will be met with understanding and without judgement.21 S&C coaches can encourage this by creating a positive and inclusive training environment where all athletes feel valued, regardless of performance levels. Simple actions, such as greeting athletes warmly, asking about their well-being and actively listening to their responses, can build up trust over time.36 Showing vulnerability – such as sharing personal challenges – can further humanise the coach and strengthen connections.26,39

Balancing high-performance demands with athlete welfare is a critical responsibility. Although S&C coaches must push athletes to achieve their best, they should remain attuned to potential warning signs of physical or mental injury. Adapting training plans to account for an athlete’s physical or mental state – for example, modifying a session for an athlete showing signs of undesirable fatigue or stress – demonstrates care and reinforces the message that well-being comes first.15 Additionally, integrating recovery strategies, psychological regulation practices, or opportunities for autonomy into the training process may help athletes maintain their mental health alongside their physical performance.34

By cultivating trust and prioritising athlete welfare, S&C coaches can act as a vital bridge between performance and well-being, supporting athletes to thrive both on and off the field.

Effective collaboration within a multidisciplinary team is essential for supporting athletes’ performance and mental health.28 As part of this team, S&C coaches can play a crucial role in fostering connections with sports psychologists, medical staff, and other support personnel to ensure a holistic approach to athlete care.45 Building strong relationships with sports psychologists and other specialists requires proactive communication and a shared understanding of each professional’s role.50 Regular meetings or informal check-ins can help establish trust and ensure everyone is aligned on athlete priorities. For example, S&C coaches might liaise with sports psychologists to tailor physical training sessions that complement mental skills work, such as using imagery or breathing techniques.45 Open channels of communication are critical to the success of the multidisciplinary team.13,50 Importantly, this may allow for early identification of potential issues, enabling the team to intervene effectively before problems escalate.

Advocating for a coach-athlete-centred approach27 further enhances collaboration and promotes better outcomes. As Jowett highlights,27 when coaching is framed as a mutually empowering relationship, its effectiveness is rooted in the dynamic partnership between coach and athlete. This conceptualisation fosters a shared sense of purpose, where both parties contribute to and benefit from the process, enhancing performance, well-being, and satisfaction. S&C coaches can embody this by prioritising genuine relationships built on trust and positive intent, ensuring that the athlete feels valued as an active participant in their development. For instance, in situations where an athlete reports struggling with external pressures, such as academic stress, the coach can work with the multidisciplinary team to adapt training plans in a way that aligns with the athlete's needs while maintaining long-term performance goals. By integrating the athlete’s voice into decision-making, the team demonstrates a commitment to their holistic well-being rather than short-term performance outcomes. This reinforces the notion that success is not simply measured in wins or records but in the quality of the coach-athlete relationship and the athlete's overall sport experience.29

Ultimately, effective team collaboration and a coach-athlete-centred approach create an environment where athletes feel supported, understood, and empowered to excel.

S&C coaches often have consistent contact with athletes, putting them in a unique position to notice changes in mood, behaviour, or performance. By understanding key indicators, utilising effective screening tools, and establishing clear referral pathways, S&C coaches can play a vital role in recognising early signs of potential struggles.

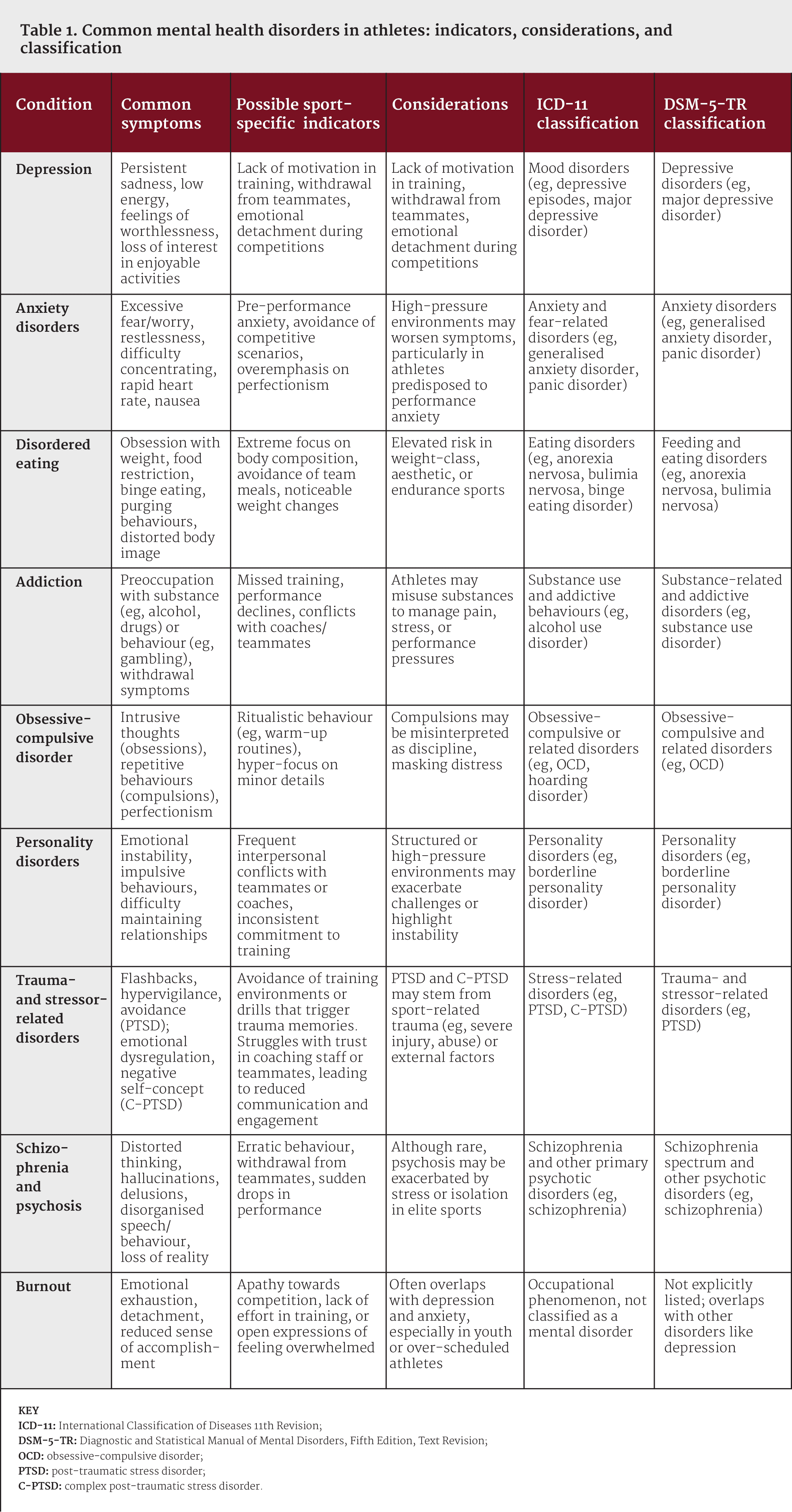

Table 1 highlights common mental health disorders in athletes, offering insights into common symptoms, sport-specific indicators, and internationally-recognised classifications.1,56 These distinctions help identify conditions that may impact athletic and personal functioning.

Identifying athletes at risk of mental health challenges requires attention to both general behavioural and emotional changes as well as sport-specific factors. Although overt signs such as withdrawal or mood changes may be noticeable, subtler indicators like fluctuations in performance, training consistency, or social engagement often require deeper observation. General signs may include sadness, irritability, fatigue, difficulty concentrating and social withdrawal. These may manifest in ways that are less directly observable, such as poor focus during training or an increase in perfectionistic tendencies. Sport-specific signs may include declines in performance, heightened pre-competition anxiety, or avoidance of high-pressure situations. Overtraining or undertraining, unexpected injury patterns, or emotional distress during setbacks can also signal deeper struggles.

As previously discussed, certain sport-specific circumstances can elevate the risk of mental health challenges. This may include injury,16,46 periods of transition (eg, changing competitive levels, teams, or adapting to a new training environment),42 retirement,19,48 and periods of underperformance.37 However, key life events are also important risk factors.3,19,46 Non-sport stressors, such as bereavement, relationship difficulties, or financial pressures, can intersect with the demands of training and competition. Coaches should be cognisant of changes in athletes’ circumstances outside of sport.

Athletes with neurodiverse conditions (eg, ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, or specific learning disorders such as dyslexia) may face unique challenges, such as heightened sensitivity to stress, difficulties with transitions, or the additional mental load of managing their condition.24 Although neurodiversity often comes with strengths – eg, hyper-focus or creative problem-solving – athletes in environments that fail to accommodate their needs may be at a higher risk of mental health struggles. Creating inclusive, supportive spaces and promoting a strengths-based approach is likely important to minimising these risks.

By understanding these indicators and the associated risk factors, coaches can play an active role in supporting athlete well-being, acting as a bridge between performance settings and professional mental health care when needed.

Screening tools and structured observation protocols can facilitate proactive identification of at-risk athletes. Although S&C coaches may not diagnose mental health conditions, currently utilised tools such as wellness questionnaires can provide insights into an athlete’s current state. Daily interactions with the athlete should also be used to monitor for changes in mood and readiness.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) have developed two specific resources for the purpose of identification of at-risk athletes:18

1. The Sport Mental Health Assessment Tool 1 (SMHAT-1) for sports medicine physicians and other licensed professionals, and

2. the Sport Mental Health Recognition Tool 1 (SMHRT-1) for athletes and their entourage.

They have also developed the Mental Health in Elite Athletes Toolkit25 as a more general resource to help athletes and practitioners. The SMHRT-1 provides some possible experiences (eg, thoughts, feelings, behaviours, physical changes) which may indicate mental health concerns.

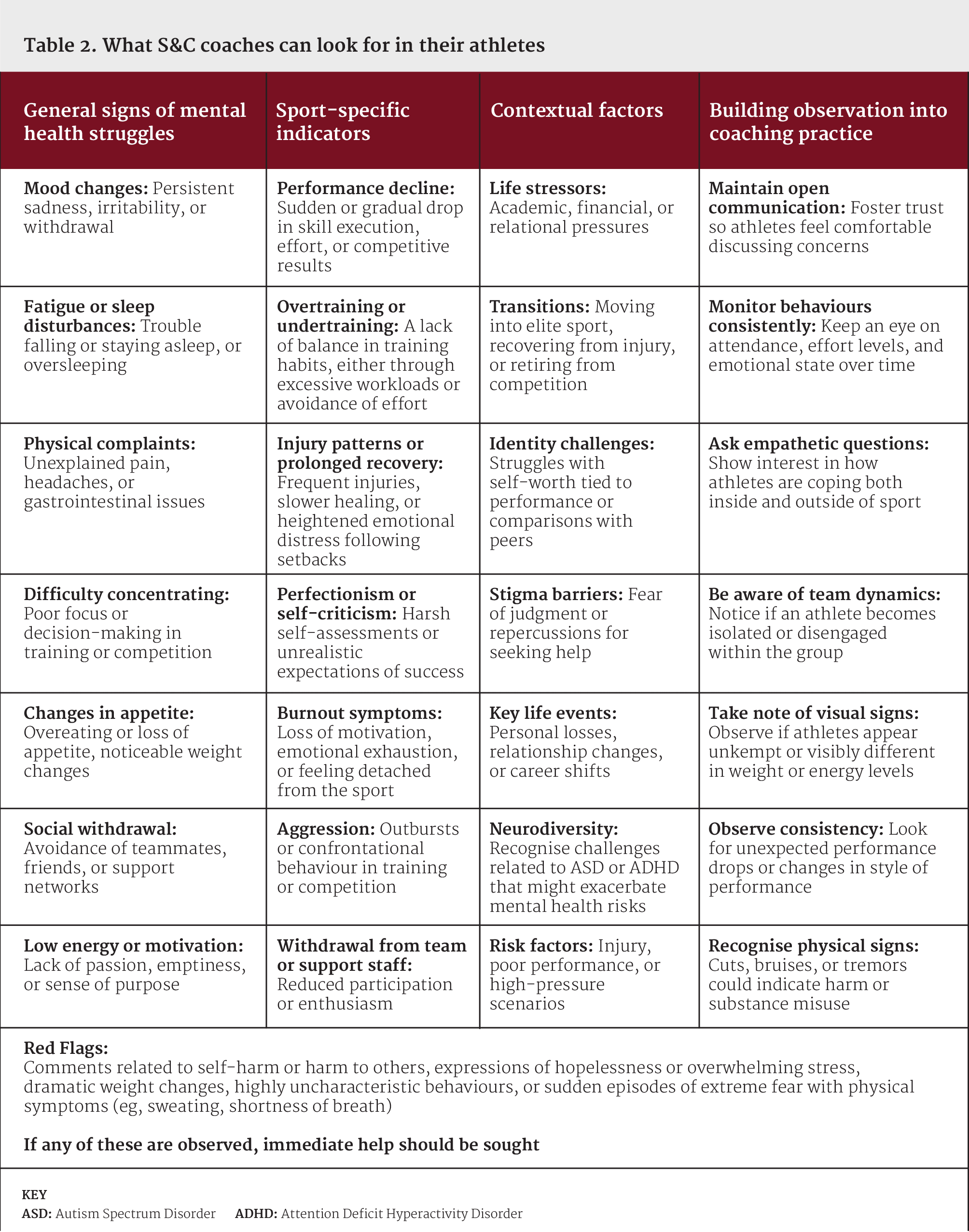

Table 2 provides practical guidance for S&C coaches on what to observe in their athletes, offering examples of general signs, sport-specific indicators, and contextual factors to consider. Building observation into regular coaching practices, such as monitoring attendance, effort levels, and emotional state, ensures athletes’ well-being remains a priority.

When concerns are identified, having clear referral pathways ensures athletes receive appropriate care.18 S&C coaches cannot treat mental health problems, but they can play an essential role in recognising concerns, providing initial support, and facilitating access to appropriate care with qualified professionals.6 Thus, building relationships with mental health professionals and establishing referral processes are key steps in addressing mental health challenges effectively.21

A key component of effective pathways is establishing an effective Mental Health Action Plan (MHAP) within the club or organisation.25 This plan should outline clear steps for handling urgent situations, such as identifying a mental health first aider or the team doctor as the first points of contact. It may also signpost to specific mental health professionals such as psychiatrists or clinical psychologists with expertise relevant to the condition (eg, addiction, eating disorders, etc). Of course, in emergency situations, contacting the emergency services is critical. Coaches must also respect the athlete's autonomy in non-emergency cases, offering support and education about available resources without forcing treatment.

For children or vulnerable adults, primary caregivers must be included in the process to ensure appropriate decisions are made. Confidentiality should be maintained where possible, but safeguarding responsibilities take precedence if there is a risk of harm to the athlete or others. S&C coaches must adhere to relevant organisational policies and legal requirements, balancing transparency with caregivers and the athlete's right to privacy. When in doubt, consulting with safeguarding officers or mental health professionals is essential in order to navigate sensitive situations appropriately.

Recognising that an athlete is struggling is the first step; however, how coaches respond can significantly influence the athlete’s willingness to seek help. By initiating open, non-judgmental conversations and practising active listening, S&C coaches can create a safe and supportive environment.21,25,53

Approaching athletes in a calm, private setting is essential for meaningful dialogue. Coaches should avoid making assumptions or minimising the athlete’s concerns and instead focus on expressing care and curiosity. A simple yet effective opening statement might be: ‘I’ve noticed you don’t seem like yourself lately. Is everything okay?’ This demonstrates empathy and signals that the coach is there to support, not judge.

Recommendations for initiating these conversations:

Active listening fosters trust and helps athletes feel genuinely heard,15 which can be therapeutic in itself. This involves more than just hearing the words: they must feel understood and valued.

Key techniques may include:

By creating an open, judgment-free space and practising active listening, coaches set the stage for the next steps in supporting struggling athletes. Importantly, these initial steps can empower athletes to articulate their concerns and begin considering solutions, with the coach positioned as a trusted ally.

When athletes face mental health challenges, aligning performance goals with mental health needs becomes critical. Support plans often require collaboration across a multidisciplinary team, including the athlete, S&C coach, sports coach, sports psychologist, and other relevant professionals. Effective communication and role clarity are essential to ensuring that interventions are cohesive and address the athlete's specific needs.50 Working with sports coaches and sports psychologists may enable the integration of mental health strategies into wider or more typical performance frameworks. Thus, mental health care can be tailored to the athlete’s sport-specific demands. For example, managing anxiety in competition or addressing self-confidence issues during training.

Central to any support plan is the athlete themselves. Autonomy should be a key focus for the S&C coach36 and is highlighted as an important factor in the management of mental health concerns.55 Although mental health struggles can sometimes diminish a sense of control,4 empowering the athlete to participate actively in the development and refinement of their intervention fosters engagement and efficacy.

Adjusting training demands is often necessary when athletes experience problems with mental health: high training loads can often negatively influence mental health.2,33 It is therefore reasonable to suggest that high physical or psychological stress from training can exacerbate mental health challenges. Strategic load management allows coaches to align physical preparation with the athlete’s mental state, ensuring both short- and long-term well-being while maintaining their connection to the sport.

Promoting self-care is a powerful way for S&C coaches to support athletes in maintaining their mental health.6 Encouraging healthy coping mechanisms and advocating for recovery strategies empowers athletes to develop skills for managing stress and maintaining balance in their lives. This process is especially important in performance-driven environments, where athletes may neglect recovery and personal well-being in pursuit of their goals.

Educating athletes on the value of recovery strategies – such as sleep,49 nutrition,12 mindfulness practices,38 and relaxation techniques41 – helps integrate these habits into their routines. For instance, guided mindfulness or breathing exercises may reduce pre-competition anxiety, while promoting good sleep habits can improve mood and performance. Coaches can lead by example, normalising discussions about recovery and self-care as integral to athletic success.

Encouraging help-seeking behaviours is equally vital.6,21,25 Normalising the use of professional resources, such as sports psychologists and mental health professionals, can remove stigma and encourage athletes to seek support early. The S&C coach plays an important role here by providing information about available resources and reassuring athletes that reaching out for help is a sign of strength, not weakness.

Despite the growing recognition of the importance of mental health in sports, several challenges can hinder S&C coaches’ ability to fully integrate these strategies into their practice. One significant barrier is the stigma surrounding mental health, both within sporting cultures and among athletes themselves. Many athletes may be reluctant to disclose struggles for fear of appearing ‘weak’ or jeopardising their place on a team. Similarly, S&C coaches may feel they lack the training or confidence to approach mental health topics effectively, fearing they might ‘say the wrong thing’ or overstep professional boundaries.

Another barrier is the time and resource constraints within many training environments. S&C coaches often work within high-pressure settings where performance metrics dominate discussions, leaving little room to prioritise mental health interventions. Additionally, not all organisations have access to mental health professionals or resources, limiting referral pathways and collaborative opportunities.

Overcoming these barriers requires both systemic changes and individual efforts. Moving forward, S&C coaches can take on more advocacy roles within their teams and organisations, promoting the integration of mental health into the broader performance framework. This includes working to normalise mental health discussions, pushing for the inclusion of mental health resources and collaborating with other professionals to develop comprehensive athlete care plans.

The role of technology also presents an exciting opportunity. Wearable devices, apps and digital platforms are increasingly being used to monitor physical performance and recovery, but they could also be adapted to track mental wellness indicators like sleep, mood, or stress. By leveraging these tools, S&C coaches can gain deeper insights into athletes’ overall well-being and tailor training programmes accordingly. Importantly, these make it easier for the coach to initiate discussions with the athlete on a personal level.

Finally, the profession must continue to evolve through education and training. More widespread adoption of mental health certifications and ongoing professional development can empower coaches to feel confident in supporting athletes, ensuring that they remain vital allies in bridging the gap between mental health and performance.

S&C coaches are uniquely positioned to act as proactive allies in safeguarding and promoting athletes' mental health. Their regular, close interactions with athletes provide opportunities to recognise early signs of mental health challenges, initiate supportive conversations and integrate mental health considerations into training plans. By taking a proactive, empathetic approach, S&C coaches can play a key role in fostering environments that prioritise both performance and well-being.

The strategies outlined in this article offer practical ways to support athletes effectively, from active listening and collaborative support plans to promoting self-care and encouraging help-seeking behaviours. By embedding these practices into their coaching philosophy, S&C coaches can contribute to athletes’ overall success both on and off the field.

In an increasingly demanding sporting landscape, the integration of mental health and performance is not just beneficial, it is essential. S&C coaches have the tools to make a meaningful difference, creating environments where athletes can thrive physically and mentally.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Edition, Text Revision). Washington, DC. 2022.

2. Angeli A, Minetto M, Dovio A, and Paccotti P. The overtraining syndrome in athletes: A stress-related disorder. J Endocrinol Invest 27: 603-612. 2004.

3. Arnold R and Fletcher D. A research synthesis and taxonomic classification of the organizational stressors encountered by sport performers. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 34: 397-429. 2012.

4. Bergamin J, Luigjes J, Kiverstein J, Bockting CL, and Denys D. Defining autonomy in psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13: 801415. 2022.

5. Bilgoe SC, Janse van Rensburg DCC, Goedhart E, Orhant E, Kerkhoffs G, and Gouttebarge V. Unmasking mental health symptoms in female professional football players: a 12-month follow-up study. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 10: e001922. 2024.

6. Bissett JE, Kroshus E, and Hebard S. Determining the role of sport coaches in promoting athlete mental health: a narrative review and Delphi approach. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 6: e000676. 2020.

7. Blakelock DJ, Chen MA, and Prescott T. Psychological distress in elite adolescent soccer players following deselection. J Clin Sport Psychol, 10: 59-77. 2016.

8. Castaldelli-Maia JM, Gallinaro JGME, Falcão RS, Gouttebarge V, Hitchcock ME, Hainline B, Reardon CL, and Stull T. Mental health symptoms and disorders in elite athletes: a systematic review on cultural influencers and barriers to athletes seeking treatment. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53: 707-721. 2019.

9. Dorfling T and Fulcher ML. High prevalence of harmful drinking habits and gambling among professional rugby players: mental health symptoms and lifestyle risks among New Zealand Super Rugby players—a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 10: e002002. 2024.

10. Edmondson AC. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm Sci Q, 44: 350-383. 1999.

11. Edmondson AC and Lei Z. Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1: 23-43. 2014.

12. Firth J, Gangwisch JE, Borsini A, Wootton RE, and Mayer EA. Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing? Br Med J, 369: m2382. 2020.

13. Fletcher D and Wagstaff CRD. Organizational psychology in elite sport: Its emergence, application and future. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10: 427-434. 2009.

14. Foskett RL and Longstaff F. The mental health of elite athletes in the United Kingdom. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 32: 765-770. 2018.

15. Foulds SJ, Hoffmann SM, Hinck K, and Carson F. The coach-athlete relationship in strength and conditioning: high performance athletes' perceptions. Sports, 7: 244. 2019.

16. Golding L, Gillingham RG, and Perera NKP. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in high-performance athletes: a systematic review. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 48: 247-258. 2020.

17. Gorczynski PF, Coyle M, and Gibson K. Depressive symptoms in high-performance athletes and non-athletes: a comparative meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51: 1348-1354. 2017.

18. Gouttebarge V, Bindra A, Blauwet C, Campriani N, Currie A, Engebretsen L, Hainline B, Kroshus E, McDuff D, Mountjoy M, Purcell R, Putukian M, Reardon CL, Rice SM, and Budgett R. International Olympic Committee (IOC) Sport Mental Health Assessment Tool 1 (SMHAT-1) and Sport Mental Health Recognition Tool 1 (SMHRT-1): towards better support of athletes’ mental health. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55: 30-37. 2021.

19. Gouttebarge V, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Gorczynski P, Hainline B, Hitchcock ME, Kerkhoffs GM, Rice SM, and Reardon CL. Occurrence of mental health symptoms and disorders in current and former elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53: 700-706. 2019.

20. Gucciardi DF, Hanton S, and Fleming S. Are mental toughness and mental health contradictory concepts in elite sport? A narrative review of theory and evidence. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 20: 307-311. 2017.

21. Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, and Christensen H. Barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking for young elite athletes: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 12: 157. 2012.

22. Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Mackinnon A, Batterham PJ, and Stanimirovic R. The mental health of Australian elite athletes. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18: 255-261. 2015.

23. Hill DM, Cheesbrough M, Gorczynski P, and Matthews N. The consequences of choking in sport: A constructive or destructive experience? The Sport Psychologist, 33: 12-22. 2018.

24. Hoare E, Reyes J, Olive L, Willmott C, Steer E, Berk M, and Hall K. Neurodiversity in elite sport: a systematic scoping review. BMJ Open Sport & Execise Medicine, 9: e001575. 2023.

25. International Olympic Committee. IOC Mental Health in Elite Athletes Toolkit. Lausanne, Switzerland, 2021.

26. Ito A and Bligh MC. Feeling vulnerable? Disclosure of vulnerability in the charismatic leadership relationship. Journal of Leadership Studies, 10: 66-70. 2017.

27. Jowett S. Coaching effectiveness: the coach–athlete relationship at its heart. Current Opinion in Psychology, 16: 154-158. 2017.

28. Jowett S. The coach-athlete relationship within a crossboundary team of experts: a conceptual analysis. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2024.

29. Jowett S and Poczwardowski A. Understanding the Coach–Athlete Relationship, in: Social Psychology in Sport. S Jowett, D Lavallee, eds. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2007, pp 3-12.

30. Junge A and Feddermann-Demont N. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in top-level male and female football players. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 2: e000087. 2016.

31. Kegelaers J, Wylleman P, Defruyt S, Praet L, Stambulova N, Torregrossa M, Kenttä G, and De Brandt K. The mental health of student-athletes: a systematic scoping review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17: 848-881. 2024.

32. Kew ME, Dave U, Marmor W, Olsen R, Tsai SHL, Kuo LT, and Ling DI. Sex differences in mental health symptoms in elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Health. 2024.

33. Kreher JB and Schwartz JB. Overtraining syndrome: a practical guide. Sports Health, 4: 128-138. 2012.

34. Kuettel A and Larsen CH. Risk and protective factors for mental health in elite athletes: a scoping review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13: 231-265. 2020.

35. Kuettel A, Pedersen AK, and Larsen CH. To Flourish or Languish, that is the question: Exploring the mental health profiles of Danish elite athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 52: 101837. 2021.

36. Maloney SJ. Engage, Enthuse, Empower: A framework for promoting self-sufficiency in athletes. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 45: 486-497. 2023.

37. Mesagno C, Hammond AA, and Goodyear MA. An initial investigation into the mental health difficulties in athletes who experience choking under pressure. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 74: 102663. 2024.

38. Myall K, Montero-Marin J, Gorczynski P, Kajee N, Sheriff RS, Bernard R, Harriss E, and Kuyken W. Effect of mindfulness-based programmes on elite athlete mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57: 99-108. 2023.

39. Nienaber A-M, Hofeditz M, and Romeike PD. Vulnerability and trust in leader-follower relationships. Personnel Review, 45: 567-591. 2015.

40. Parry KD, Braim AG, Jull RE, and Smith MJ. No longer a sign of weakness? Media reporting on mental ill health in sport. International Journal of Sport Communication, 17: 171-181. 2023.

41. Pelka M, Heidari J, Ferrauti A, Meyer T, Pfeiffer M, and Kellmann M. Relaxation techniques in sports: A systematic review on acute effects on performance. Performance Enhancement & Health, 5: 47-59. 2016.

42. Pilkington V, Rice S, Olive L, Walton C, and Purcell R. Athlete mental health and wellbeing during the transition into elite sport: Strategies to prepare the system. Sports Medicine Open, 10: 24. 2024.

43. Prinz B, Dvořák J, and Junge A. Symptoms and risk factors of depression during and after the football career of elite female players. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 2. 2016.

44. Purcell R, Pilkington V, Carberry S, Reid D, Gwyther K, Hall K, Deacon A, Manon R, Walton CC, and Rice S. An evidence-informed framework to promote mental wellbeing in elite sport. Frontiers in Psychology, 13: 780359. 2022.

45. Radcliffe JN, Comfort P, and Fawcett T. The perceived psychological responsibilities of a strength and conditioning coach. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 32: 2853-2862. 2016.

46. Rice SM, Gwyther K, Santesteban-Echarri O, Baron D, Gorczynski P, Gouttebarge V, Reardon CL, Hitchcock ME, Hainline B, and Purcell R. Determinants of anxiety in elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53: 722-730. 2019.

47. Rongen F, McKenna J, Cobley S, and Till K. Do youth soccer academies provide developmental experiences that prepare players for life beyond soccer? A retrospective account in the United Kingdom. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 10: 359-380. 2021.

48. Sanders G and Stevinson C. Associations between retirement reasons, chronic pain, athletic identity, and depressive symptomsamong former professional footballers. European Journal of Sport Science, 17: 1311-1318. 2017.

49. Scott AJ, Webb TL, Martyn-St James M, Rowse G, and Weich S. Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev, 60: 101556. 2021.

50. Stewart P, Fletcher D, Arnold R, and McEwan D. Exploring perceptions of performance support team effectiveness in elite sport. Sport Management Review, 27: 300-321. 2024.

51. Sundgot-Borgen J and Torstveit MK. Prevalence of eating disorders in elite athletes is higher than in the general population. Clin J Sport Med, 14: 25-32. 2004.

52. Taylor J, Collins D, and Ashford M. Psychological safety in high-performance sport: Contextually applicable? Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4: 823488. 2022.

53. Vella SA, Mayland E, Schweickle MJ, Sutcliffe JT, McEwan D, and Swann C. Psychological safety in sport: a systematic review and concept analysis. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17: 516-539. 2024.

54. Walton CC, Rice S, Hutter RIV, Currie A, Reardon CL, and Purcell R. Mental health in youth athletes: a clinical review. Advances in Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, 1: 119-133. 2021.

55. World Health Organisation. World Mental Health Report: Transforming mental health for all. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation. 2020.

56. World Health Organisation. International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision (ICD-11). Zurich, Switzerland. 2022.

Sean is the founder of Maloney Performance, a high-performance strength and conditioning service supporting athletes and teams across multiple sports. He also leads Palestra Education; a coach development initiative focused on translating sport science and pedagogical principles into practical learning.